Finland, home to one of the most progressive tax systems in the world. But how much is too much?

From Nokia executives to other multi-millionaires, the Nordic country of Finland is not shy to impose hefty fines if need be. The latest infraction to join this list was a reported €121 000 speeding ticket for a motorist driving at 82km/h at a 50km/h zone last Summer. The amount was calculated based on disposable income, prior infractions and the size of the infraction.

Finland is not the only country famous –or infamous for those with a lead foot– for exorbitant speeding tickets. In 2010 the story of a purported over 1 million euro speeding fine in Switzerland made headlines.

In economics, a tax system that allocates fines and taxes based on income is known as a progressive tax system. Rather than a regressive tax that strips away proportionately more from low-income households, a progressive tax is tailored to each taxpayer’s ability to pay.

On paper, a progressive tax allows for a more equal society by redistributing income from higher cohorts to those in need. If the equivalent of a multi-millionaire’s week’s worth of daily income can be used to fund the refurbishment of a local hospital, the fine can be said to benefit society as a whole. It levels the playing field, assuring that each citizen faces comparatively equal punishments.

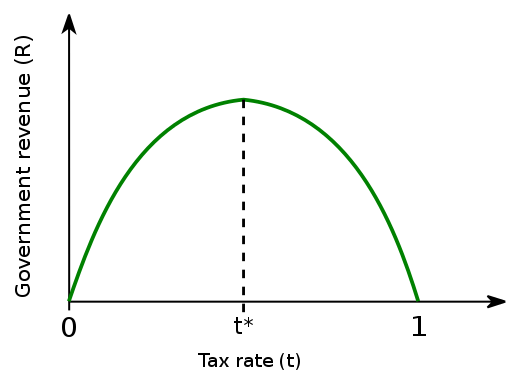

But that begs the question: how much is too much? Surely, after some point a fine or a tax reaches its upper bound in usefulness to society – after which the marginal benefits derived from it begin to fall. American economist Arthur Laffer recognized this problem and coined the Laffer Curve.

The Laffer Curve displays how the optimum tax rate of t* maximizes government revenue. After this point, individuals start to lose economic incentive to progress in their careers as the government takes a higher proportion of their income. A study from 2017 found that out of 27 assessed OECD countries, 5 were operating beyond the optimum tax point: Denmark, Sweden, Belgium, Austria and Finland. Economic theory would hence suggest that, all else being equal, these countries would benefit from a lower tax rate.

Nevertheless, these countries are amongst the most developed and equal nations in the world. First, some clarifications: overall, their tax systems are not even the most progressive in the world. That title could, arguably, go to the United States.

For starters, poor single-parent households have to contribute a far greater proportion of their income in Nordic countries than their American counterparts. Moreover, the regressive Value Added Tax (VAT) that is commonplace in most of the world is not present at a federal level in the US. As outlined by The Economist, much of the US’s progressiveness comes from tax deductions given to low-income households.

And yet, the United States sits at the bottom of the Gini coefficient index (that measures disparity within a country) for OECD countries both pre- and after taxes. The other aforementioned nations cruise comfortably in the top 10, with Sweden being the only outlier for ulterior reasons.

The main difference between these countries and the United States is that, on average, the upper bound for how much rich people are taxed is much lower in the US. The same study that placed Finland beyond the optimum point in the Laffer Curve placed the United States last, only after Slovakia and Mexico, in terms of the gap to the optimum point.

It clearly displays that rich people could be taxed far more in the United States. However, higher taxes are not as popular as tax deductions. Instead of taxing both the rich and the poor and making sure that income from higher tax brackets is used to fund welfare programs, the US has seemingly opted for a more popular compromise: to let the rich keep their money and to give tax breaks to those who need them.

With this philosophy, the gaping government budget deficit is not that surprising. An unwillingness to tax lobbyists and those in power combined with a lackluster welfare system results in one of the most progressive tax systems also being the most unequal.

Nordic countries and other developed economies are able to foster equality and welfare through apt government expenditure and welfare systems. It has forged a culture that appreciates the civic duty to contribute to one’s society, recognizing that helping the worse-off does not come solely from tax deductions but is supported by functioning social systems and help networks.

Though a single parent has to pay more in taxes in Finland, they receive greater social security, aid such as the famous maternity package (“baby box”) and better support to take time off work. If that means some funds have to be obtained from speeding millionaires, so be it.

Leave a comment