The Wall Street Crash of 1929 set off one of the largest market panics in modern history. What made the Great Depression Great, however, was monetary policy.

Great, as former Fed chair Ben S. Bernanke aptly pointed out, is a prefix you typically wouldn’t be too pleased to see in economics. The Great Depression of the 1930s, the Great Inflation of the 70s and the Great Recession of the late 2000s are all defined by their profound negative implications to the world economy. The significance of the Great Depression is especially striking, as it is often cited as the crucial catalyst that fomented the economic and political instability during the far-right’s rise to power in interwar Germany.

The Great Depression

For a summary on the Great Depression, keep reading. Else, skip to the next section.

What started as the rupture of a stock market bubble that had been building up during the “roaring twenties” quickly became an unmitigated disaster as both consumer and business confidence plummeted. If the Wall Street Crash was the lighter, a lack of centralised deposit insurance was the fuel that together resulted in nationwide bank runs in the United States.

Depositors rushed to pull their money from failing banks that, with no means to pay for the sudden increase in withdrawals, resulted in almost 10 000 bank failures during the banking panics of 1931-33–a figure that would come to define the Great Depression. Within a span of a couple of years, the world’s strongest economy had been brought to its knees, with a record unemployment rate of nearly 25% in 1933 and negative growth and prices both dropping to as low as -10% YOY. Talk about animal spirits.

Where there is smoke, there is fire––and firefighters. So where was the Federal Reserve?

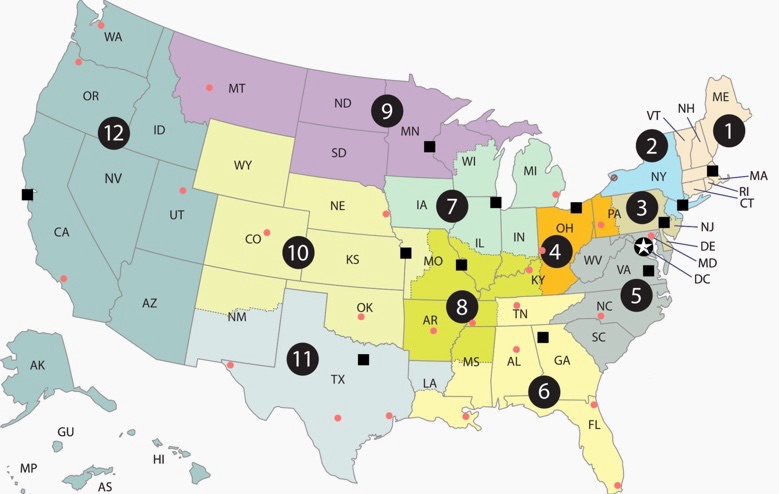

The still sprouting institution found itself in hot waters in the eve of the Great Depression: having bounced back from a series of short recessions in the 20s, it was largely unequipped to deal with a recession of such magnitude. The Federal Reserve system, comprised of 12 different districts that are still in place today, lacked the regulatory ability to set a standardised monetary policy across the country. Much of it instead fell within the remit of each individual district, which was even more problematic for states split between two policy areas. Remember this detail, as it’ll become important later.

Being on the cusp of a tidal wave of new economic thinking didn’t help either. Macroeconomic theory and the role of policy intervention was an especially heated point of contention within academic circles, aggravating division and indecisiveness during the crisis. Keynes’ landmark book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money that would forever set the tone in favour of anti-cyclical policy was all but a strand of thoughts, with prevailing wisdom favouring classical non-interventionism.

Call it laissez-faire capitalism or recklessness, as the recession worsened, the Federal Reserve contracted the money supply by raising interest rates (partly to maintain the gold standard). Reserve banks also failed to adequately support failing institutions by providing necessary liquidity. Rooted in social Darwinism’s survival of the fittest, so-called liquidationism emphasised minimal intervention and called for the weak links of the banking system to fail. In the liquidationist view, recessions were necessary to purge the financial system of systemic risks and to expose any banking malpractices.

That’s usually where the story ends. The Fed, believing in a brutish doctrine, failed to deliver on its mandates and exacerbated an already brewing crisis. In 1933 Roosevelt suspended the gold standard that had pegged monetary policy’s effectiveness, and in 1934 he introduced deposit insurance (FDIC) to quell bank runs–turning the tide on the depression.

But this wouldn’t be called a deep dive if it would end here, so strap yourself in.

I’ve become interested in the question of finding ‘by how much’ the Fed worsened the Great Depression. More specifically, the exact role a lack of liquidity provision played in the sky-high number of bank failures. This is where the different Federal Reserve districts come into play. Remember: many aspects of monetary policy were controlled by individual districts and, as it would turn out, not all districts opted to disregard their ‘lender of last resort’ obligations.

After parsing through records from the Great Depression, a discrepancy between liquidity provision arose. The districts of New York (2nd) and Atlanta (6th) were comparatively progressive in policy, whilst all others were notoriously strict in their lending. Though far from an even split, this difference provides a good base to compare the impact of different policies.

What’s more, states such as Mississippi, Tennessee and Louisiana were split between the differing doctrines–you can’t ask for much better control variables! Commercial banks along the district border in Mississippi that were under stricter lending (d. 8th) did in fact show comparatively higher failure rates than those under loose policy (d. 6th). But does this trend stack up elsewhere?

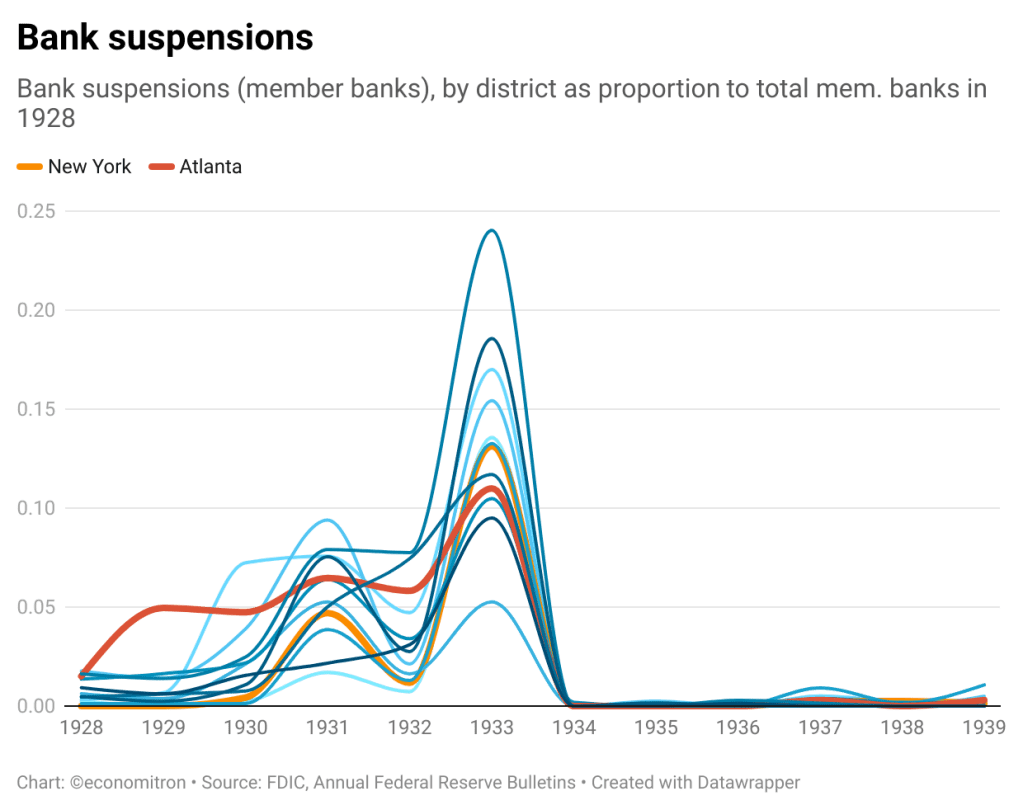

In the chart below, I have compiled the total number of member bank suspensions as a proportion to the total number of banks for all 12 districts. So how did commercial banks do under our good cops, New York and Atlanta?

All districts displayed the expected two waves of bank failures that occurred during the banking crises of 1931-33, with 1933 being a markedly bad year that saw around 4000 suspensions. As for New York and Atlanta, they did indeed perform better than their neighbours (presumably on account of their looser lending): Atlanta’s adjacent districts of St. Louis and Richmond scored an average of 45% more failures in their peak (weighted in regard to their total bank populations in ‘28, as always). The prevailing consensus within economic historians is that New York also performed “well” thanks to its mitigation. This takes into account that NY was the epicenter of the Great Depression.

Nothing short of a full-blown regression analysis that accounts for demographics, trade flows, banking system dynamics etc. will give an exact estimate, but this one is close enough (maybe a task for some other time!). A split of 2-10 is also less than ideal for comparisons, which is why most analyses on the effect on mitigation compare districts one-on-one. Nevertheless, comparing all districts side-by-side is more fun, and contrasting based on geographic vicinity still shows that supplying commercial banks with liquidity to quell banking panics did likely result in fewer failures.

One last thing: what about moral hazards? The question that originally had sent me delving into liquidity provision records was whether looser policy incurred any negatives down the line. To be specific, I wanted to know if being “soft” with banks encouraged them to take more risks (hence resulting in so-called moral hazards). Providing loose liquidity makes it also more likely for weaker institutions to slip through the cracks and to survive the crisis–resulting in systemic risks liquidationists believed were recessions’ job to eliminate.

The water for measuring moral hazards is murkier. For one, it’s hard to recognize malpractices, as they often go undetected; it’s also harder to separate variables when looking at what caused a bank to fail. Nevertheless, the next chart plots bank failures from 1934 onwards, this time as a proportion of 1934 bank figures. The drop between 1933 and ‘34 is dramatic due to (as you’ll remember) the implementation of deposit insurance in 1934.

Note: percentage as compared to total member banks of each district in 1934

This time around no clear difference arises between New York, Atlanta and the other districts. Liquidity provision likely played an insignificant role in these later failures, as districts with similar policy profiles had differing outcomes. The timeframe would also ideally be greater, but the advent of WW2 blurs later 1940’s data.

To answer the question

As has been shown, a dogmatic fixation on maintaining money supply stable caused unnecessary bank failures and worsened the crisis. Our two outliers, New York and Atlanta, showed moderately-to-substantially fewer bank failures most likely because of their laxer policy. This stance also likely did not cause meaningful ripple effects later on.

However (and this is a big however), of the roughly 9000 banks that failed during the Great Depression, only about 2500 belonged to the Federal Reserve system. The rest? Nonmember banks. These were banks that were not under the close scrutiny of the Fed (not that members were either, at least compared to today’s standards). Though today two-thirds of US banks are still nonmembers, the regulations they face are on par with member banks. So, in a way, the Fed was vastly limited in what it could do.

So, did monetary policy cause the Great Depression? Yes, and no. The Great Depression was waiting to happen: the boom during the 20’s had led to an overvalued stock market that was going to burst in any moment. A complete disregard to banking supervision and stability didn’t help either. Where monetary policy did fail was precisely in believing that the depression was unavoidable and even necessary to correct “the excesses of the twenties” (Bernanke, 2012).

Even if most banks were nonmembers, the most important institutions (namely state member banks) remained under the Fed’s control: leaving them out to dry neglected the central bank’s responsibilities and fomented instability across the system. The Great Depression, just as the Great Inflation 40 years later and the Great Recession another 40 years onwards, serves as a lesson and as a reminder of what to do and of what not to do in the face of a crisis. Ultimately, the Great Depression is a lesson on misguided policies, tunnel vision and a system built to fail. The subsequent reforms on deposit insurance, banking supervision and the entire philosophy surrounding monetary policy are proof of learning from mistakes. Learning form mistakes that ought not to be forgotten, for to forget is to risk repeating.

Leave a comment