Politicians typically deal in 4-year cycles. Economists don’t.

Trump’s re-election has once again brought to public attention the ever-growing threat posed by national debt levels. As governments’ pandemic spending frenzies start becoming a distant memory, the reality of sky-high debt levels ought to have an instant sobering effect on governments planning to max out their administration’s credit cards. The issue? Budget deficits do not seem to be going anywhere.

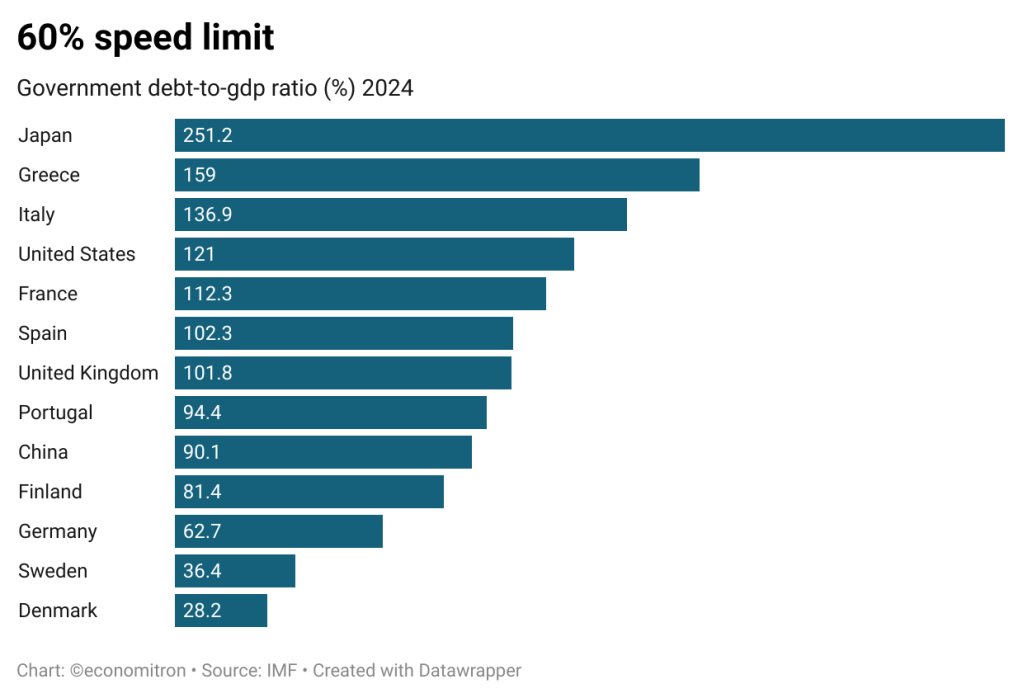

100% means that it would take the entire value of all output produced in 1 year within a country to pay off debt.

The United States’ soon-to-be 47th president has on numerous occasions promised to roaring, cheering and clapping crowds that he will extend income tax cuts, implement caps on tax deductions, as well as (contrary to Harris) cut both corporate and income taxes further. These promises seem to be based on the naively misguided assumption that fewer taxes will be compensated by higher tariffs. Whilst both candidates’ proposals widen the level of national debt, Trump fares far less stellarly.

The reason for such reckless disregard for fiscal soundness is pitifully clear. In election cycles not spanning farther than a few years, promising fiscal austerity, responsible fiscal policy and deleveraging is a one-way street to political suicide.

Democracy’s inherent risk of falling into a populist tyranny of the majority is, in many ways, as old as democracy itself. In the Ancient Greek state of Athens, the first cracks of the imperfect system started to appear when state decisions became skewed towards generous government handouts to citizens, liberal borrowing schemes and funding for festivals. This trend is ongoing today, with politicians exploiting economic illiteracy to garner votes.

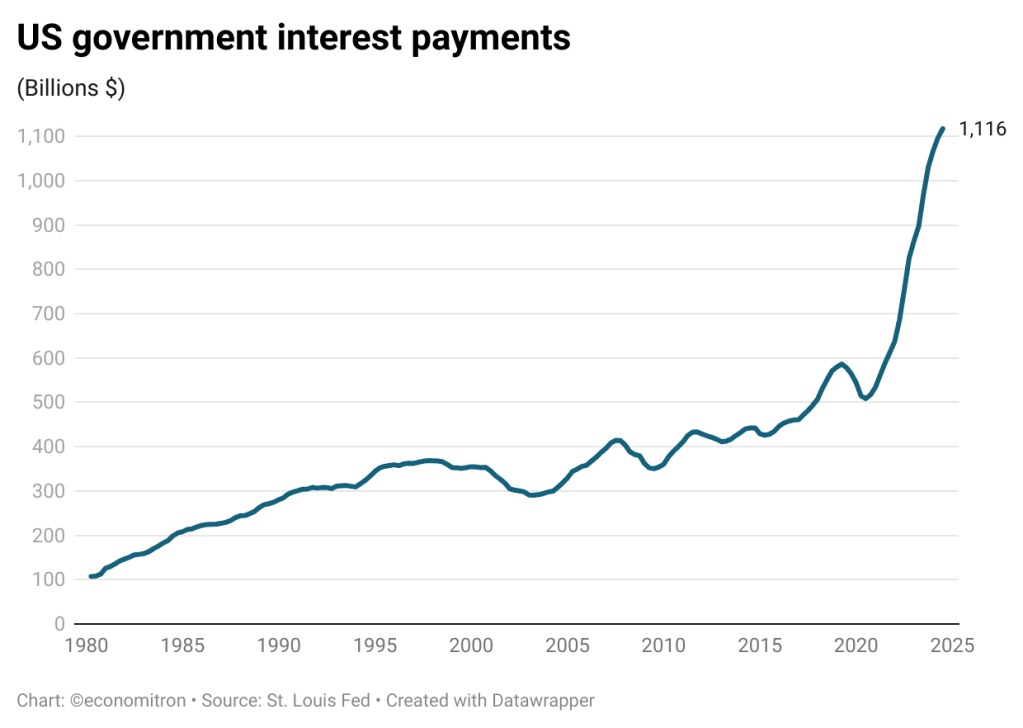

Who bears the blunt of rising debt payments? Usually it is future generations’ job; this time debt burdens risk being too great to postpone indefinitely.

And if you’re looking for a fright, look up what a graph of a ‘Minsky Moment’ looks like.

Structural budget deficits in the face of exorbitant national debt is a problem not unique to the US. French bond markets have just come off from a surge in yields originating from unconvincing budget restructuring plans. German chancellor Olaf Scholz fired his finance minister over the latter’s refusal to extend the government’s spending plans. China’s government spending is skyrocketing as it tries to pull the country out of an economic crisis stemming from the collapse of its property sector. It’s just a matter of time before sovereign bond yields across the world start rising as investor risk increases.

The world is normalising governments’ attitude of ‘shop till you drop’. It’s not only becoming commonplace, but countries are being pressured to supercharge their industries lest they be left behind in competitive global markets. Generous Chinese subsidies have prompted the US to follow suit. Now, under Mario Draghi’s report on competitiveness, the EU needs an additional investment of €800 billion annually to close the gap between its competitors, finance the green transition and bolster its defence. Germany’s finance minister was sacked over a dispute on €9bn, for reference.

National politics has proven to be a flawed channel through which a government’s finite sums are allocated. Though spending (be it on defence, healthcare or infrastructure) reflects what democratic voters find important, a world full of populist rhetoric is ineffective at dealing with the political hot potato of spending cuts, especially at the scale that is required—just ask Liz Truss.

Here we arrive at a conundrum. It is abundantly clear that the EU’s spending goals will not be met under the status quo. The only logical next step, complementing Europe’s monetary union, is to bind member countries’ budgets under common borrowing and spending.

This fiscal union would increase accountability and set far greater confidence for borrowing, driving down the natural rate of interest on sovereign bonds. Extending the banking union and installing a capital markets union would also enhance the EU’s cross-border investment and factor mobility. Most importantly, divesting budget control to a supranational level takes away administrations’ political burden of clamping down on spending, as well as uniting Europe’s business cycles (a huge bonus for monetary policy).

Whether this plan and level of collaboration is politically feasible remains to be seen. Countries in Europe are already pointing daggers at each other, feeling (understandably) that certain member states benefit far more than they contribute to the EU. In times of tension akin to those during the sovereign debt crisis, it is hard to foresee collaboration happening.

Whilst removing governments’ unabated power over borrowing still leaves room for national policies on allocating spending in certain areas, loss of sovereignty will be an unavoidable setback in achieving the fiscal union—if you’re economically minded, this may not be a concerning trade-off.

And to those still defending national governments’ ability to set national spending, I ask: whatcha gonna do when the IMF comes looking for you.

Addendum: the ECB “sounded alarms” on Wednesday (20.11) over growing risks of unsustainable government finances.

Update 4.12.2024: Michel Barnier becomes France’s shortest-serving prime minister after being fired over budget disputes.

Leave a comment