Dubbed by The Economist as the “bleakest week in Europe since the fall of the Iron Curtain” (Europe’s Worst Nightmare, 22.02.25), things have as of recent taken a turn for the worse.

NATO members have been jolted awake by a deteriorating transatlantic relationship, which has been described as parasitic by some. This has been highlighted in both scheduled and impromptu meetings between world powers. In Europe, a pitiable sense of impotence has washed over leaders as they fend off internal divisions whilst hastily drawing up plans for the future of their continent. The magical words on everyone’s minds?

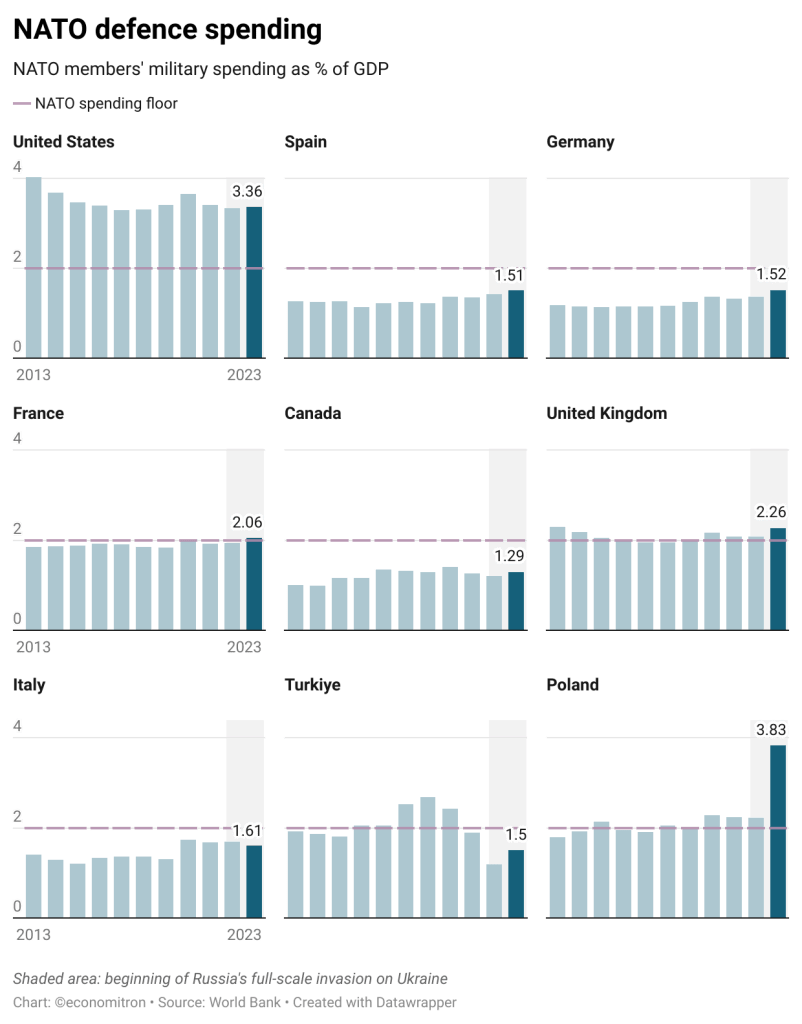

Coming from a country where half of the discretionary budget is spent of defence, NATO’s largest spender has been adamant that others ramp up their contributions. The 2% of GDP spending floor agreed upon over a decade ago has largely been ignored, leaving the alliance in a precarious spot as money faucets are under threat of being shut off. This threat has reignited talks for joint borrowing in the EU.

EU countries thread a thin line. On one hand (and if anything), budgets should start normalising as the pandemic’s expansionary fiscal policy is left in the rearview mirror. Funds need to be channeled to combat structural productivity issues and pull the eurozone out of stagnation. And yet, the EU wants to scrape together hundreds of billions’ worth of military spending to bolster both Ukraine and itself.

The issue with defence spending is that its positive spillovers are scarce whilst its costs are ample. When the price tag of a battle-ready motorised army brigade can easily eclipse that of a fully kitted state-of-the-art hospital, it’s no wonder why welfare states have discretely chosen to overlook their spending obligations. Indeed, a 2024 study found arms spending to have a relatively weak multiplier effect (how much economic activity is generated for each € spent)––owing to strong import-dependence. Due to diminishing returns to scale, the more is spent the less is generated.

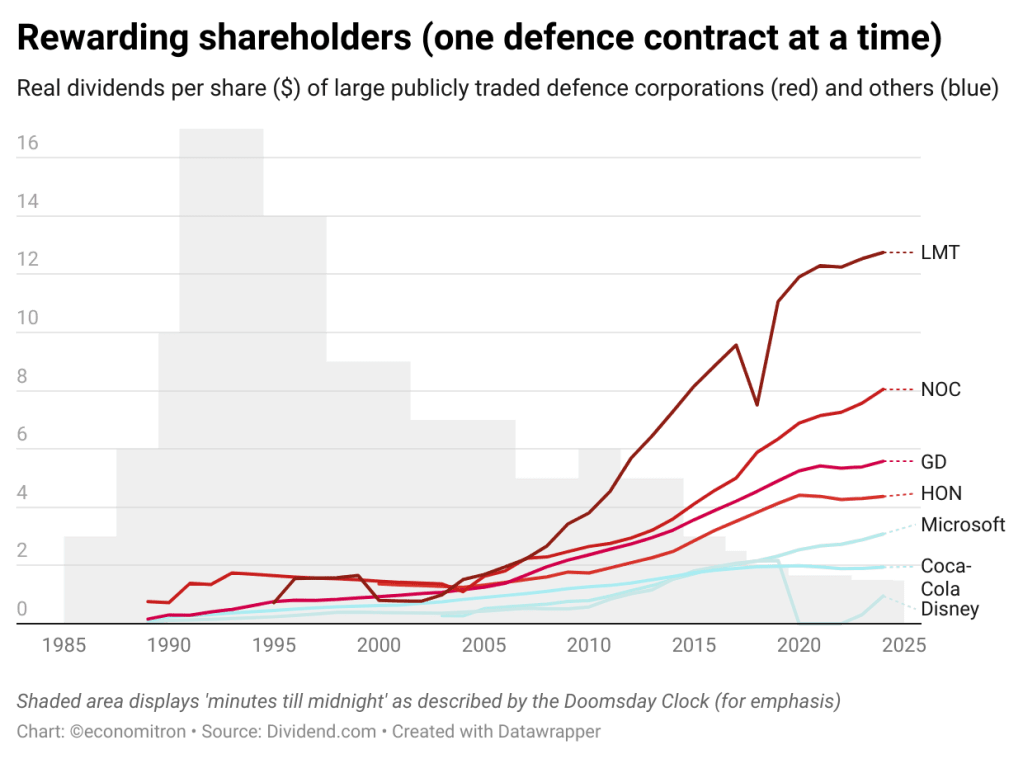

Nevertheless, war is—famously—a profitable business. As heads of states bashed their heads first in Munich, then in Paris, European defence companies’ stocks predictably soared. With no shortage of conflicts around the world, military contractors have historically had a good deal of success. They also have one of the best possible customers who, despite often being a monopsonist, offers a reliable revenue stream and is no stranger to price gouging.

With a backdrop of the Atomic Energy Agency’s doomsday clock ticking ever-so-closer to midnight (currently at its closest level since the end of WWII), defence companies have performed well. As food for thought, the chart below plots inflation-adjusted dividends from American publicly traded military corporations, along with other randomly picked firms featuring similar stock growth profiles.

Cold War-esque geopolitics pose a legitimate threat to the modern welfare state. Money to fund the unfortunate indulgences of the new world order will have to come at the expense of other spending: the possibility of discretionary spending such as in the US—where military operation and maintenance gets the same cut as healthcare, income security, education and social services combined–—is perhaps not so distant. Latest ideas to fund defence include disregarding it in maximum EU budget deficit rules calculations: too bad that creditors will come back asking for interest payments, be the debt hidden or not.

Even worse is the way countries such as Germany, the UK and France are stuck in the middle, incapable of drawing up plans due to weaknesses in their own governments. Germany’s probable next chancellor, Friedrich Merz, has nonchalantly said that the country’s constitutional debt brake will be maintained despite higher defence spending. The how is seemingly up to the reader to decide.

In Britain, Rachel Reeves’ pro-growth economic plans are at odds with straining public finances so much as to illicit austerity measures. This hasn’t stopped the rigamarole of contradictory messaging from the government, which is too scared to pull the trigger on tax rises. Luckily for her, Britain is no longer bound by EU rules, phew! (Although domestic budget decrees still apply).

If it hasn’t come across clearly enough, one cannot help but feel a sense of disillusionment with the current state of affairs. As the liberal world crashes and burns, instead of sobering up and taking charge of the wheel, political parties are too busy fighting incompetence whilst being flanked by the rise of the extremes. This post (in an economics blog) has dabbled into politics not by choice, but because politics has intruded with economics. Nevertheless, in a world defined by uncertainty, one thing is for certain: whilst countries run around like headless chickens, defence companies are in for some prosperous years.

Leave a comment