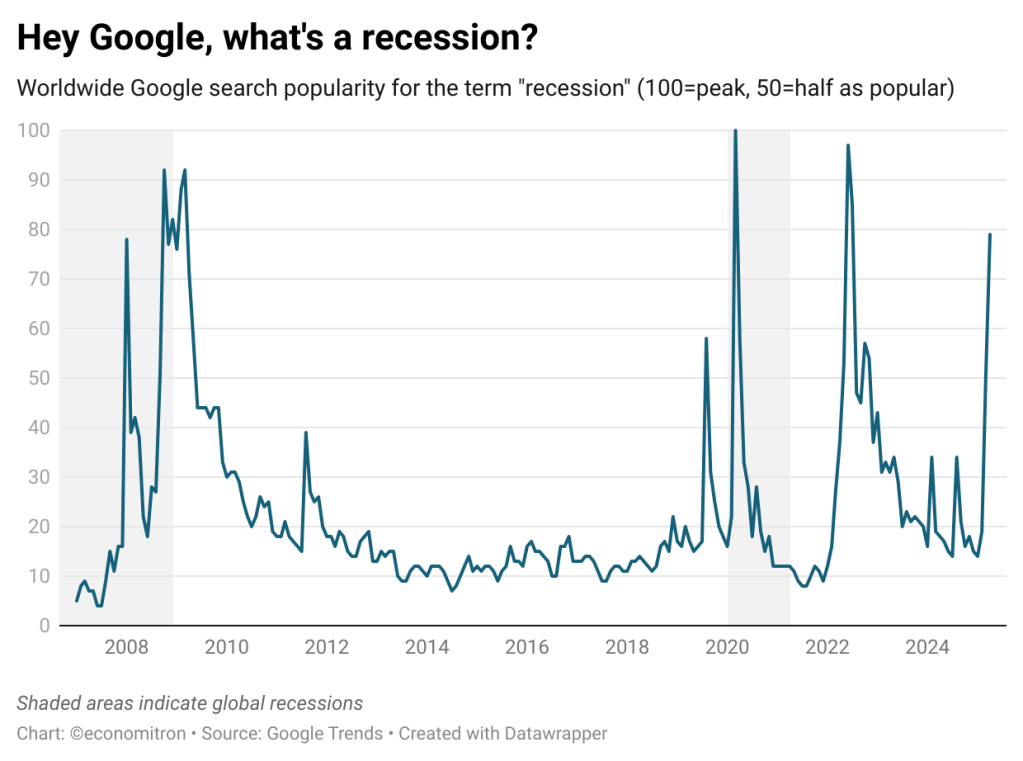

Just as recession fears were being left in the rear-view mirror, a Trump-shaped sunshade has cast doubts over a soft landing.

The recent flurry of remarkable “acts of self-harm” from the world’s biggest economy has sparked discussions that would have felt nonsensical just a few months ago. It is safe to say that the decline of world order was in very few people’s radars—and even unexpected for the architects of this destruction, I posit. Once in a lifetime events would usually be fun, if it was not for the fact that in the context of economics, this rarely equates to good news.

Raising the United States’ effective tariff rate to a level not seen for a hundred years—and for no apparent reason, no less—seem like the events of a poorly written comedy for those with a sardonic sense of humour. But this is real life, and unlike movies, reality has consequences that cannot be escaped by rolling out the final credits. What’s more, postponing part of these tariffs has only added to the market malaise by fueling uncertainty.

To see just how remarkable this shock risks being, I want to compare the United States to one of recent history’s most prolongued and damaging economic crises. As pointed out by The Economist, in the 1990s Japan faced a dangerous combination of a simultaneously (i) plunging stock market, (ii) rising government debt servicing costs and (iii) depreciating currency. What started as a series of asset bubble bursts turned into a cycle of sticky deflation in what are known as the country’s “lost decades”. This time, the United States faces the risk of economic stagnation with tariff-induced inflation and out-of-hand government spending—only that now, pinpointing the source of the crisis is far easier.

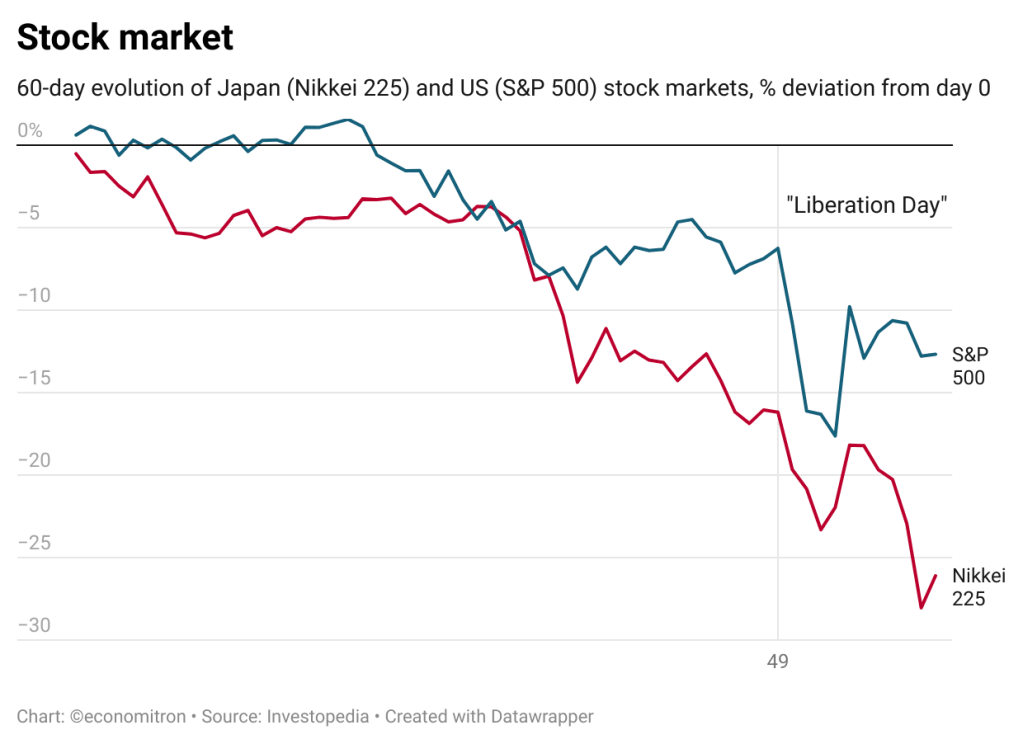

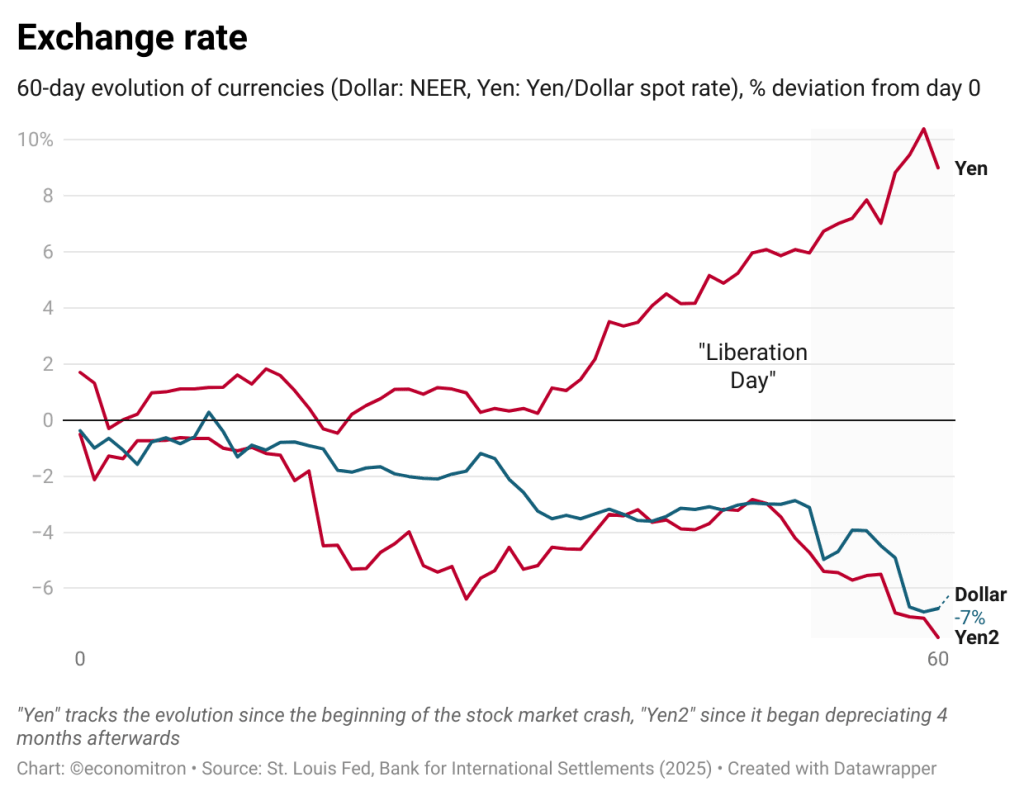

For the comparisons, the charts below plot the day-by-day development of different indicators compared to the baseline of a so-called day 0.

First up, stocks. A good gauge of not only current market sentiments but of expectations for the future. Taking the new administration’s inauguration day to be day 0 for the US, and setting the day the Japanese stock market peaked prior to its crash (December ’89) for Japan’s baseline, both economies display similar trends. The tumble in the American index is especially remarkable on the so-called “Liberation Day” when trade restrictions where announced. Whilst in Japan stocks kept falling and falling afterwards, the start is not looking too good for a president who took remarkable pride in a booming market during his first administration.

Government officials may be willing to overlook a bear market, but the party stops as soon as the cost of taking out debt starts rising—a drug many economies are hooked on. Rising yields on government bonds reflect investors’ risk premium as spending plans look unsustainable, or lawmakers’ actions start resembling unserious business. Indeed, it is a “yippy” reaction (his words) from bond markets that prompted the partial and temporary rollback of trade restrictions. With a need to refinance $9tn worth of debt within the next year, even the slightest jump in yields can be the difference between tens of billions more spent. Until now, however, the US has evaded the vast increases in Japan.

Usually, rising government bond yields are met with a short-term appreciation of the nominal exchange rate. As investors seek higher rewards, so-called “hot money” flows into a country to buy up higher yield assets denominated in the domestic currency, thus boosting its value. This is exactly what happened in Japan in 1990, as Japanese investors began reshoring their capital. In fact, it took 4 months after the crash for the currency to finally begin depreciating (“Yen2” on the graph).

The United States has not been given this grace period. Higher yields on government borrowing reflect a bond sell-off (driving down their price and increasing the yield) as investors dump dollar-denominated assets. Depending on what indicator is used, the USD has depreciated by between 6 to 9% against baskets of currencies from other countries. Although this may be hailed as a victory for those seeking to boost export competitiveness, the underlying story reflects a global retreat from the world’s reserve currency. A weaker dollar is also an additional headache facing those worried about diminishing purchasing power.

Once a robust pillar of global financial flows, supported by its competitive economy and respect for the rule of law, the US finds itself being pulled apart by strong currents. Being aware of parallelism with past economic disasters is important, as it highlights the true dangers of the risks at hand. Although a decade-lasting recession is not expected on the horizon, what is expected no longer means anything in a world that disregards all logic.

Trump is famously a fan of professional wrestling. One can only wonder if he is as big a fan of the 3-punch combination striking America’s economy.

Leave a comment