The Single Market is the single biggest success of European integration. It also encapsulates everything that is wrong with the European Union.

The European Single Market is the world’s biggest internal market. Built on the four fundamental freedoms of the movement of goods, capital, services and people, it ensures the stream of factors of production between 31 sovereign European countries. Through the common market, member states can enjoy the benefits of specialisation and economies of scale. Indeed, around 70% of EU states’ trade in goods was limited to within the union’s borders in 2024.

Far from only being a free trade area, the Single Market represents a political commitment to creating a common European home. Removing barriers between member states induces the flow of both factor resources and a shared identity; one not defined by borders but by a shared dream of a stronger and more united continent.

Such were the arguments sketched on the blueprints of the European Single Market. Since its inception in 1993, it has more than doubled its membership and has delivered many of its promises. Nevertheless, it has failed to reach the heights many of its architects intended––or wished––it to.

For one, the common market is not complete. Europe remains a fragmented landscape, with the phrase “Deepening the Single Market” being among Eurocrat’s favourite buzzwords. The IMF estimates that regulation and other non-trade barriers represent a 45% and 110% tariff for goods and services respectively in intra-EU trade, for instance.

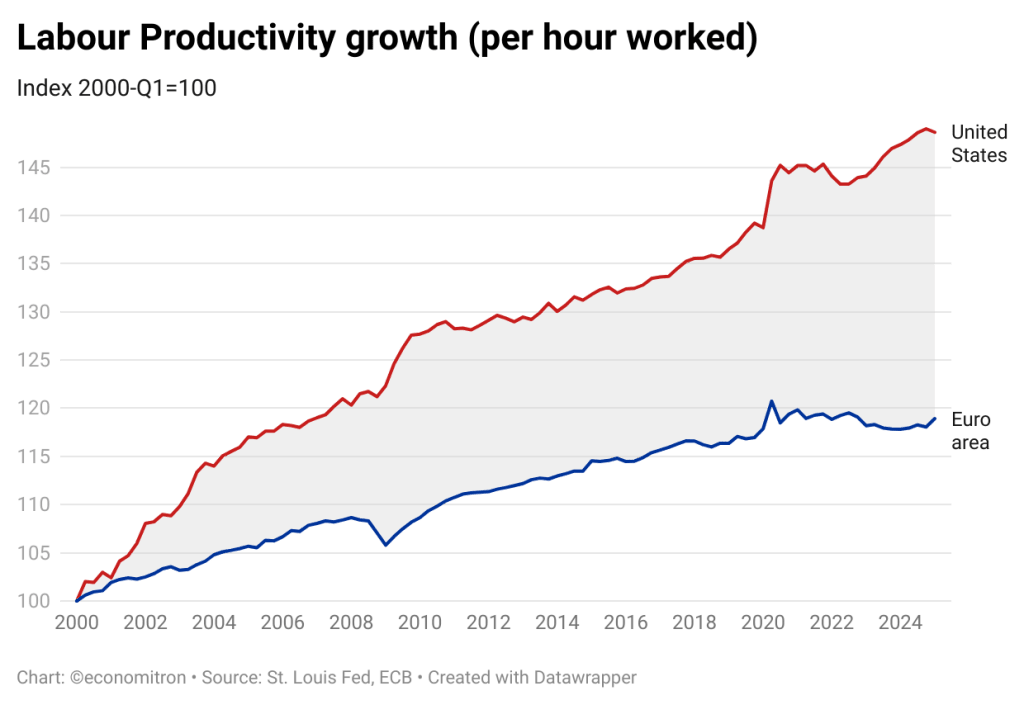

Such ailments are reflective of a larger productivity deficit in Europe. Since the early 2000s, labour productivity growth has been lackluster. Chronic demographic issues are compounded by a gap in private sector activity due to a poor investment environment. Called an open-air museum by some, it is being left behind by more agile competition: as an old joke goes, the US innovates, China replicates and Europe regulates. The continent has become reactive, awkwardly moving through the motions of a new economic world order.

On a personal note, the magnitude of the divergence became clear to me on a recent trip to the European Central Bank. Serving as a towering symbol for what European economic integration has achieved, the ECB’s headquarters are located a fair distance away from the Frankfurt city center––symbolically overlooking the skyline comprised of the city’s financial sector. Jokingly, as we looked at the view, someone remarked: American JP Morgan’s balance sheet is larger than all of theirs combined. This trend of being overshadowed in size repeats across industries. Europe’s largest company by market cap, Novo Nordisk, would not make it into the top 20 in the US––with most of its customers being, indeed, American.

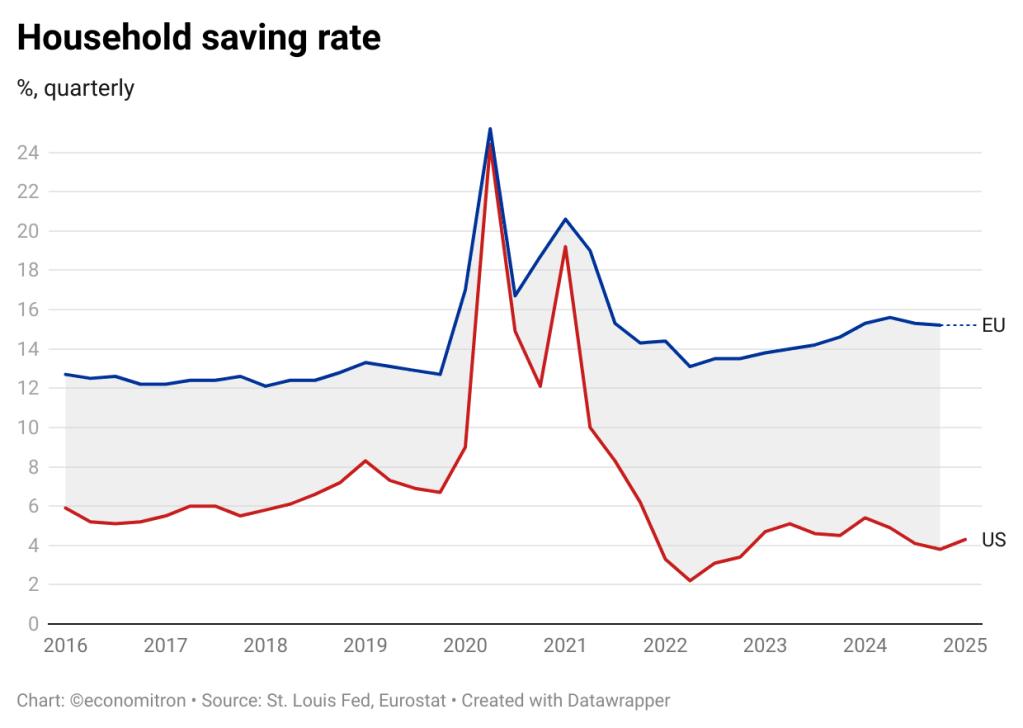

The Single Market must thus invest to become a more prominent economic figure on the global stage. In the EU, excess liquidity is held in long-term deposits, with the current household saving rate standing at an elevated level compared to other developed economies. Although excess savings exist, they do not mirror the creation of new productive capital. Indeed, venture capital investments as a share of GDP are ten times greater in the US than in the EU. The continent’s largest economy is also the world’s biggest external creditor, despite the shortage of private investment domestically. This reflects a structural lack of belief in domestic assets from an investment perspective.

Stepping up to curb the productivity deficit is imperative for both the economic and political relevance of Europe. It also has implications for the day-to-day lives of ordinary people. Capital factors have diminishing returns to scale: thus, only total factor productivity growth can sustain growing living standards without having to employ more resources that weigh on the climate.

To avoid slipping into irrelevance, the Single Market must choose to be bold and engage in necessary reforms. Fragmentation must be done away with, which pertains especially to onerous regulation. As this blog has argued for before, investment flows must be unlocked through a Capital Markets Union. This consolidates regulation regarding the transfer of capital and allows companies to access a wider array of funding not limited to one’s country.

Europeanisation is not a simple commitment. It is a time-consuming process that may not always bear fruit, such as in the case of Northvolt. In a sense, this failed solution for EU battery production (which received over €1bn in loans from the EIB) serves as a testament to why Europe must unite to confront its challenges. Public investment is key to galvanising necessary change, but the private sector has to be optimised with a better functioning Single Market. Without private investments that match and exceed government initiatives, spending such as Germany’s €1tn 10-year plan risks crowding out activity.

Nevertheless, progress in achieving these major institutional reforms has been fraught with opposition and bureaucracy. The European Council is the institution comprised of the heads of states of EU member states that gives an indication of the policy direction of the union. Looking at its quarterly meeting conclusions, interest in both the “Single Market” and mentions of “capital market” has fluctuated over the years: it grew strongest in the eve of the sovereign debt crisis, as economic divisions splintered the common market. Driven by geopolitics, we are seeing a resurgence in calls for stronger financial markets infrastructure that will support investment plans.

Europe is strong because of its institutions. But regulation in the name of consumer safety must not come in the way of creating an environment appealing to both domestic and foreign investors. Europe must also weather the existential threat of internal skepticism that has, until now, kept dreams of an ever-closer union at bay. Restoring competitiveness is the best economic policy to curb the disillusionment that causes such criticism.

In a context of global uncertainty, the stability provided by its institutions makes Europe attractive once again. Though it is full of divisions and a lack of dynamism, this also means that no single person can drastically alter things such as the block’s trade policy. Now more than ever, 74% of EU-member citizens believe that their country has benefited from the EU; 89% believe in more unity. The Single Market must leverage its qualities of trust and institutional strength to reform. Only through change will it reverse course and once again play an active role in shaping its future.

Leave a comment