Economics, like all social sciences, exists for the greater good of humankind. Economic models are tools to maintain the smooth functioning of larger systems. Their granular applications span from allocating welfare funds across regions to creating exchanges for life-saving transplants.

The movie 2001: A Space Odyssey paints a fantastical retelling of how humans leapt from the most basic tools to what we use today – and beyond. In one of its most memorable scenes, an ape discovers that a bone fragment can be wielded and used as a tool. The first-ever apparatus goes on to become a weapon.

Economics has experienced similar misuse as of late. Both degrading and misguided, what ought to be used to maximise society’s utility function has instead become a weapon to cause division.

The loudest example of this is the US’s bickering new stance on trade. Under the wrong hands, what has given the world’s largest economy its state of primacy is being used to smash every tenet of reason. The analogy with our hairy ancestors is not too far-fetched in this case.

The use of economics as a weapon can also be done with a sound moral basis. Unprecedented financial sanctions have been applied on Russian individuals, corporations and organisations that have been deemed to be complicit in the unjustified aggression against Ukraine. From seized assets, terminated contracts to price caps, western policymakers have championed a doctrine of maximum pressure in relation to Russia’s war economy — in theory.

Kremlinites are sure to be jittering as EU officials prepare to deal a decisive blow on Russian finances…with their planned 19th package of sanctions. Bystanders can only help but wonder how there are any assets left to be frozen. In all seriousness, the fact that 18 sanctions packages have come and gone serves as a testament to the realisation that (1) they have been weak and/or (2) the Russian economy has remained resilient. Indeed, both are true.

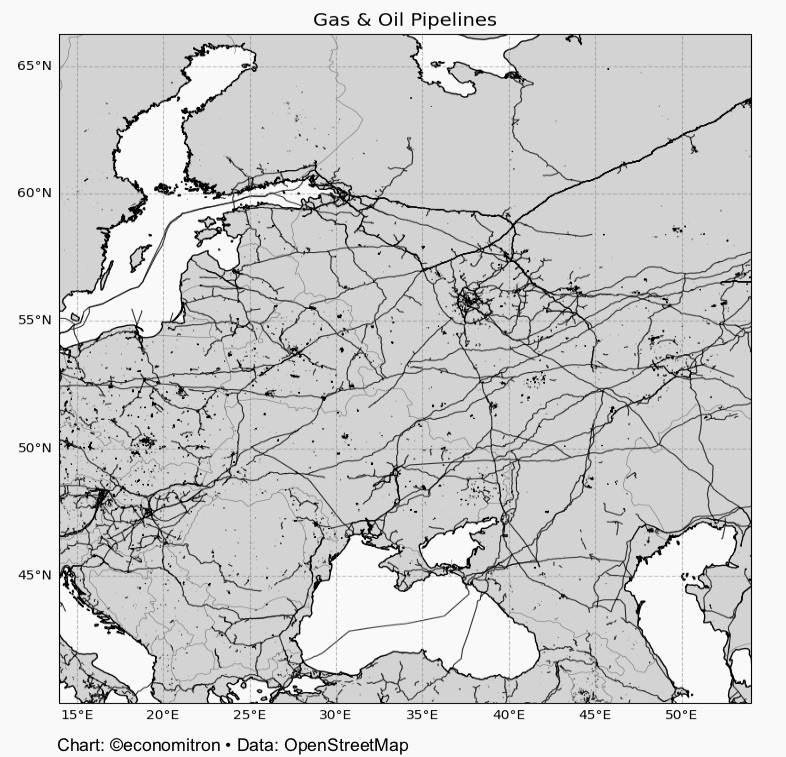

Firstly, the EU has failed to muster the unilateral will to impose harsh penalties on Russia necessary to bring about meaningful sanctions. Countries such as Greece, Hungary and Austria have remained thorns in negotiations, either worrying for penalties’ impact on their domestic industries or filling Russian coffers by skirting regulations. The circumvention of import restrictions has been well documented through channels such as Turkey and central Asia, and most if not all EU member states are complicit in this regard. Due to the continent’s energy dependency, sanctions have remained a dull weapon.

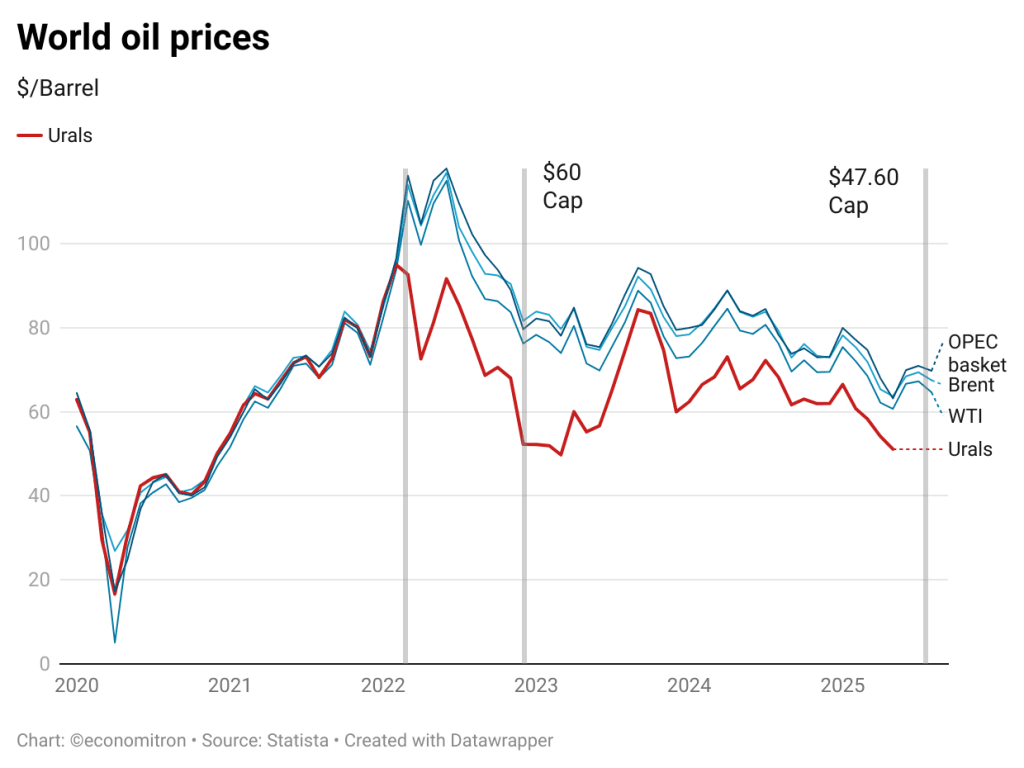

It is important to note that, to keep fuelling the war economy, Russia needs to keep its exporting industries going. Oil & gas revenues account for a third of Russia’s budget. Foreign currency inflows are thus indispensable at a time when government spending outpaces even wartime plans. Incidentally, continuous export demand from countries such as India and China keeps pushing up demand for rubles. (Though oil may be dollar denominated, forex revenues are converted into local currency once inside the country).

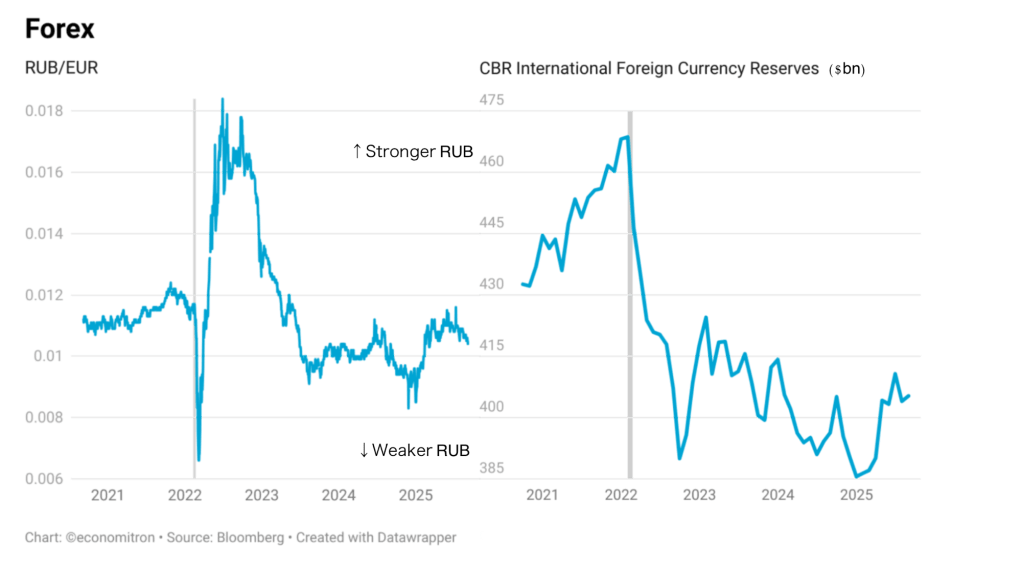

The ruble is a noteworthy point of contention when examining the country’s exports. In addition to BRICS demand, tight capital controls and a cessation of imports into the country have caused the currency to remain strong. This has hurt export revenues. A weak ruble would, however, pose an even greater threat to financial stability. Indeed, on the morning of Russia’s full-scale invasion on Ukraine, the Central Bank of Russia extraordinarily stepped into the domestic FX market to reverse course on the tumbling ruble. As luck would have it, its foreign currency reserves were at a decades high.

Engineering a Krugman-type currency crisis in a high-interest rate, capital control and ample FX reserve environment is near impossible. Despite dreadful economic fundamentals that have commercial bank chiefs shouting recession, bank losses, high fiscal deficits as well as inflation, the Russian war economy can and will keep going. With no contingency plan for the day after tomorrow, economic activity is held together by band aids provided by oil exports, applied by the Federal government and placed on the defence sector.

It is impossible to apply conventional economic weapons on an insulated adversary that operates with total disregard to both human suffering and to the longevity of their own economy. At the current –– damaging but not lethal –– rate, the west is simply alienating Russia whilst pushing the globe towards a new geopolitical world order: China has remained a major supplier of Russian arms and a lifeline to its oil exports. With talks in Brussels leading to threats of never again buying its energy, Russia is practically being shoved into Xi’s arms. Talks of a new gas pipeline between the two are ongoing.

The EU must move forcefully to penalise those who circumvent restrictions. It should follow the US’s lead and apply secondary penalties on those who trade with the warmonger. Positive incentives, such as plans to give subsidies to Chinese firms who collaborate with European counterparts, can be applied to energy cooperation too. And, if necessary, the EU and the US must not be afraid of applying less elegant tools borrowed from Trump’s trade repertoire. The lifeline to Russia remains China; the lifeline to the lethargic Chinese economy is in the hands of those who buy outbound goods. Falling prices, a slumping property sector and an all-too-high savings rate place the latter in an uncharacteristically weak position.

Unless more decisive tools are used to thwart all remaining strengths of the Russian economy, the war in Ukraine and its suffering will keep on going: good sanctions are not good if they minimise harm done to oneself whilst failing to meet their overarching purpose. Until then, our economic sanctions will keep on resembling more an ape’s blunt weapon than a clinical instrument.

Leave a comment