Government finances have been tackled from many angles in this blog. The heightened focus, or scrutiny, is well deserved. It is substantively true to characterise current noncrisis government spending patterns as something unprecedented in modern history.

The market for government obligations is remarkably interesting because of its power dynamics. The central regulator, heavily reliant debt, depends on private markets’ goodwill to keep funding its activities. And, until now, markets have been biting.

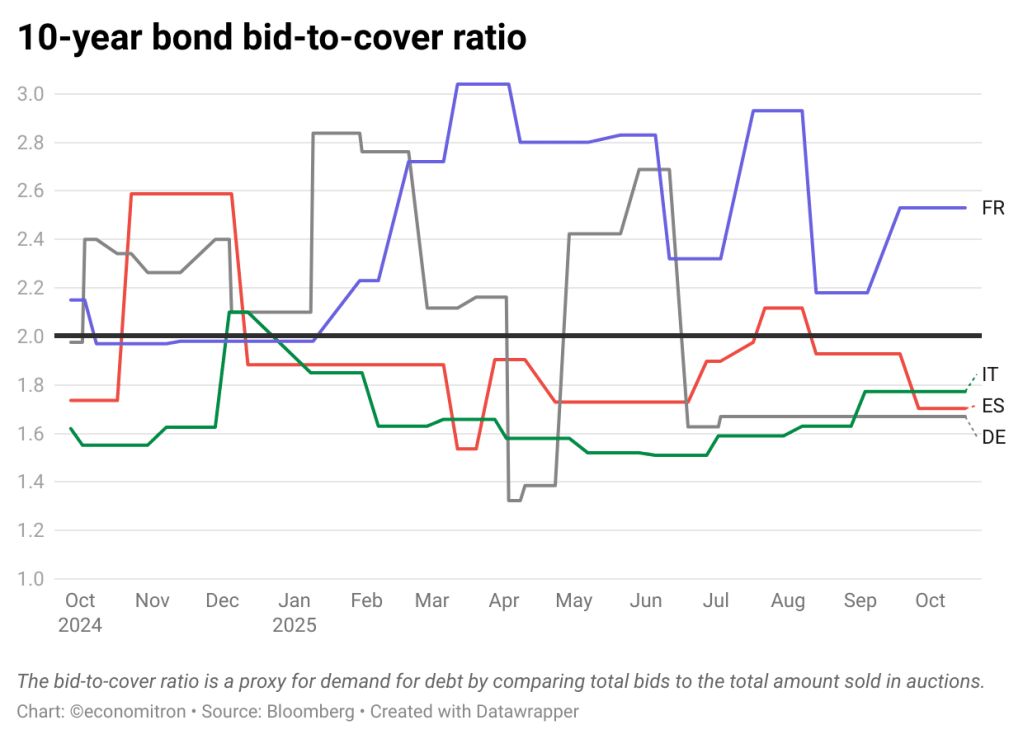

A revolving door of French prime ministers has not quelled market demand for its debt—quite the opposite, as the chart above shows. Higher borrowing costs that have accompanied three credit rating downgrades in the past year have increased investor appetite in what usually is a low margin environment.

The first conflict that arises from this is the breakdown in the system of fiscal discipline built into government debt markets. As long as there is demand for debt, any level of interest can be sustained by governments. As risk-aversion kicks in, demand should be inversely correlated with levels above junk a bond has––were it not for the case of central bank meddling.

ECB yield curve controls have been widely documented, often being contrasted with the extreme rich economy case of Japan. The truth is that quantitative easing programmes set a precedent for central banks to jump into the driver’s seat that should be occupied by the private sector. Whilst justified in some instances, the ever-looming threat of central bank intervention in the sovereign debt market is enough to (i) keep yields artificially low, allowing governments to rack up spending, or (ii) keep demand high even as risks increase (because there will always be a buyer).

Government spending also contradicts the current direction of monetary policy, providing the ECB justification enough to threaten intervention regardless of the “bailing countries out” dimension. As government bonds set a benchmark for other long-term interest rates, higher spending leading to higher yields is counterproductive in a rate cutting cycle.

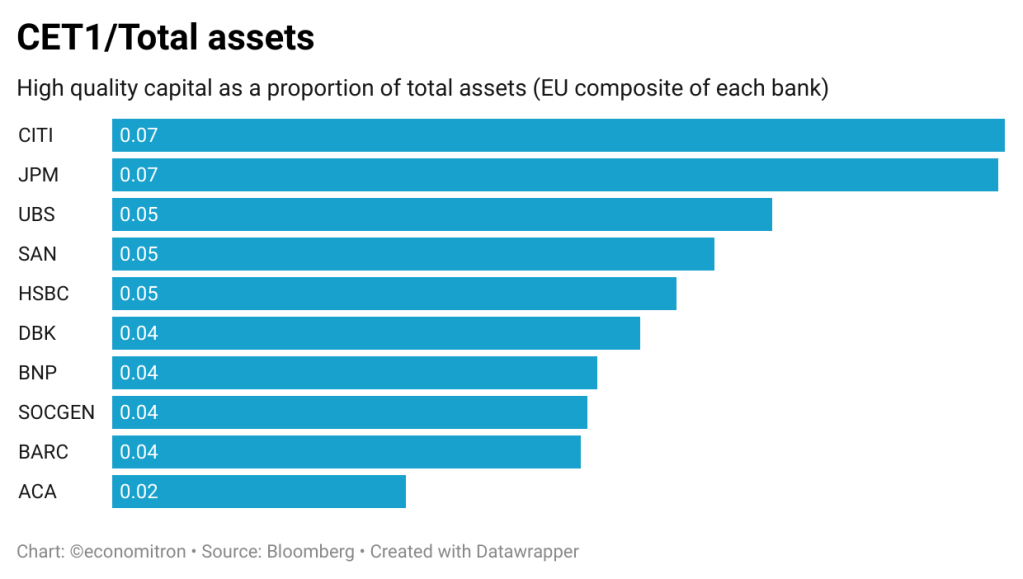

An interesting point of contention in the private sector will also be the appetite of primary dealers for rising bond issuance. These dealers are the significant institutions that are allowed to participate in bond auctions. They then offload bonds in the secondary market, facilitating the sale of billions in EU debt.

As pointed out by an ECB blog post, constrains in these dealer’s balance sheets could pose a limit to how much increased volume they will want to absorb. Some primary dealers are, as shown below, exhibiting balance sheets that are highly leveraged. Whilst this raw indicator does not show risk, the implication is that they will be growingly unwilling to stretch equity over more and more assets and dilute their buffers––thus possibly taking on fewer sovereign exposures.

For now, the private sector is stomaching government spending well. Nevertheless, cracks in the smooth functioning of the sovereign debt market raises pressure at a political level to face tough discussions about debt volumes. But progress will be difficult––just ask the five French prime ministers who have come and gone under the current presidency.

Leave a comment