Economics is a unique science. It is deeply quantitative, but most of its models, questions and datasets are normative in nature. They are not black and white, meaning that creative solutions are usually required to transform opinion-based stances into actionable models.

Out of curiosity, I wanted to see how far I could push these creative solutions. The language we use carries meanings, and these meanings can be assigned numeric values. A widely used sentiment analysis framework VADER, for instance, assigns values to words between -1 and 1 from bad to good, with 0 being a neutral word. Friendship gets assigned a value of 0.44, cute puppies 0.46, whilst uncertainty is -0.34, bad -0.54 and BAD!! 😦 -0.83.

I apply this tool to all ECB speeches from 2006 onwards. A handy well-categorised collection of speeches is provided by the ECB precisely for text analysis research purposes. The idea is that speeches given by members of the central bank’s Executive Board provide a snapshot of the hot topics and events that were going on at any given point in time. They not only include speeches tangential to official monetary policy announcements, but presentations and press interviews.

A successful analysis could show how ECB communications evolved over time, and whether they matched alternative economic sentiment indicators. This links to the role of forward guidance and the power of words, a topic which has been covered by this blog before.

With some Python coding magic, what begins as 3000 speeches quickly become 3000 well-formatted sets of readily analysable collections of words. To ensure a lack of bias, stopwords such as “and”, “the” and “furthermore” have been removed because they do not provide any insight into content. Common words such as “policy”, “inflation” or “growth” have also been removed: for instance, “HICP inflation has slowed down” could either be positive or negative depending on the wider context.

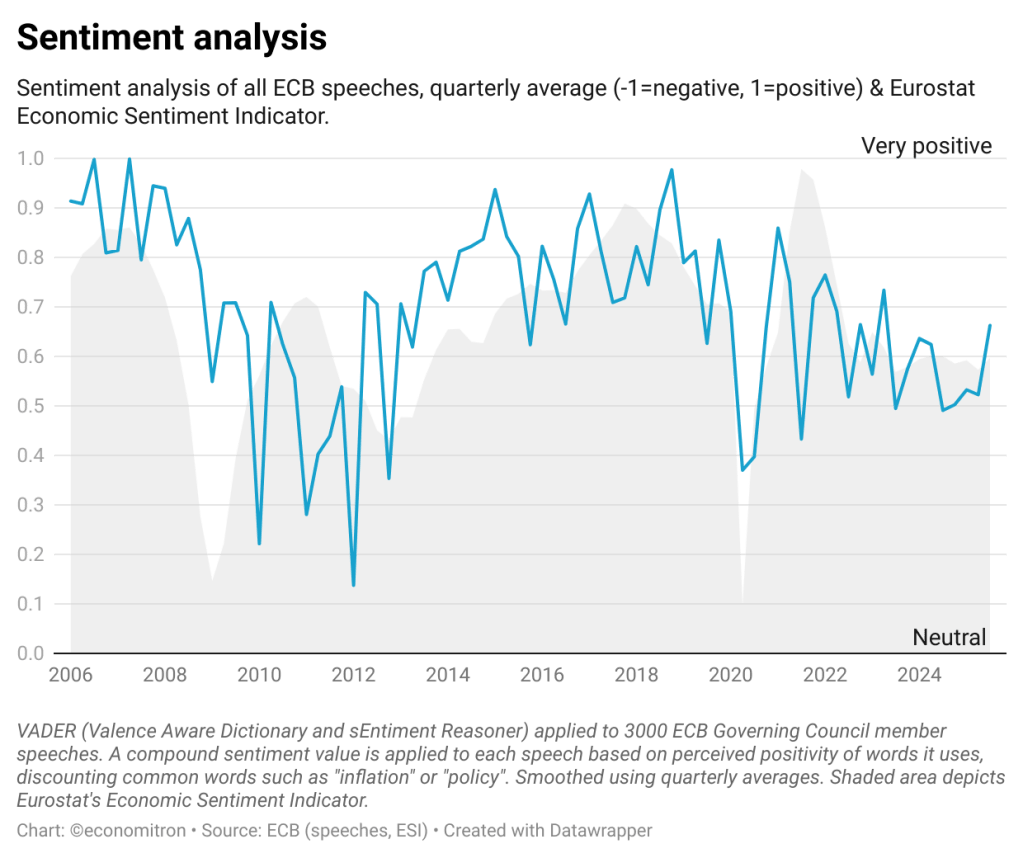

The end result is presented in the graph below. The sentiment analysis clearly shows a close tie with Eurostat’s Economic Sentiment Indicator, a survey-based assessment of the state of economic gloominess.

As expected, dips can be seen in times of crisis such as the 2008 crash or the Covid pandemic. Interestingly, the data suggest that ECB speeches were slower to become negative in the eve of the Global Financial Crisis than the ESI. They also remained cautious for a longer period as the eurozone sovereign debt crisis intensified in the early 2010s. Current sentiment levels seem to be below the historical non-crisis average, owing to growing popularity in keywords such as “uncertainty” and lacklustre growth prospects.

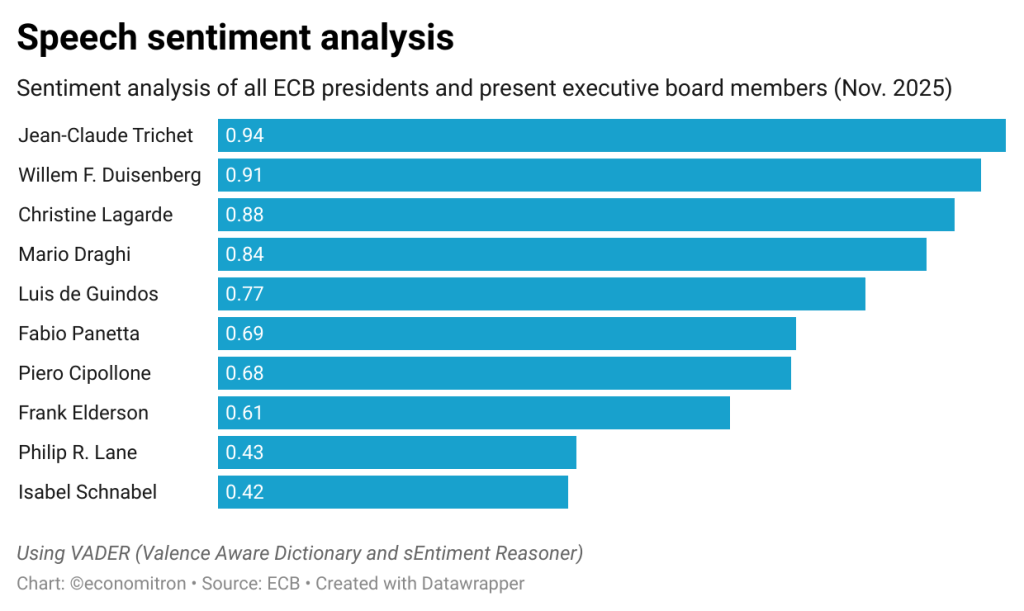

Distinguishing between speakers paints another interesting picture. Past presidents are all very positive speakers due to their role as optimistic and reassuring public figures. Meanwhile, the Governing Council’s most prominent hawk Isabel Schnabel ranks far below the total average, followed closely by chief economist Philip Lane. They are both amongst the five most negative speakers in the history of the Executive Board.

Assigning numeric values to ECB speeches has shown that they do indeed align with the economy at large. Heterogeneities between speakers exist, but the sentiment as a whole is quite positive. In future posts, it could be interesting to center the analysis around different keywords to see how topics rise into popularity and fall out of favour. What is clear is that the tip of the iceberg revealed by these text analysis tools presents many more promising research opportunities to come.

Note: the compound sentiment value of this blog post is 0.96.

Leave a comment